Railroads were newfangled technology at the beginning of the Civil War and they had not been used much in military applications. American forces had used trains to transport troops to the front during the Mexican-American War about fifteen years earlier. The railroads had grown substantially since then. At the beginning of the Civil War, the Northern territory had about 21,000 miles (34,000 km) of track while the Southern States had about 9,000 miles (14,484 km) of track.

Engine Fred Leach, U.S. Military Railroad, showing marks of cannon shot.

Photo: Mathew Brady Photographs.

War Department. Office of the Chief Signal Officer.

National Archives and Records Administration.

Still Picture Branch; College Park, Maryland.

Almost from the beginning, the armed forces of both sides of the conflict began to use the railroads to transport troops, ammunition and supplies to the front. With this newfound mobility, troops and supplies could be relocated more rapidly and in greater quantities than ever before. As the battle wore on, operations that would not have been possible without the railroads were conducted. Frequently, as the troops secured new territory, the rail system would fill in from the rear to supply the advancing troops.

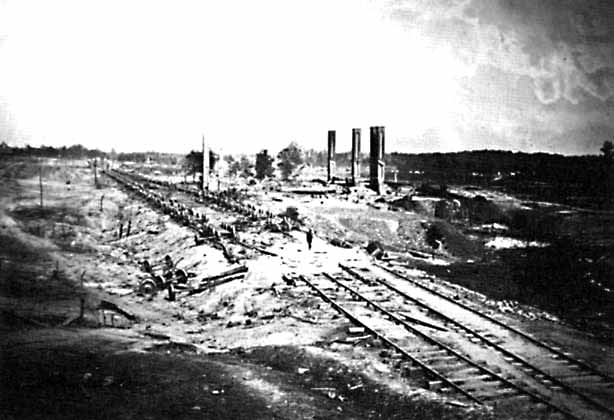

Chattanooga Railroad Roundhouse Near Atlanta.

Photo: George N. Barnard.

War Department. Office of the Chief Signal Officer.

National Archives and Records Administration.

Still Picture Branch; College Park, Maryland.

Rapid-transportation resulting from the railroad emerged as an increasingly important factor in the outcome of war. With their profound effect upon logistics, railroads influenced all military calculations including the timing of engagements and the magnitude of mobilizations. Consequently, as the war progressed, military campaigns were directed against centers of rail-transportation such as Chattanooga, Atlanta and Manassas Junction.

Destruction of Hood's Ordnance Train Near Atlanta, Georgia, 1864.

Photo: George N. Barnard.

War Department. Office of the Chief Signal Officer.

National Archives and Records Administration.

Still Picture Branch; College Park, Maryland.

Because the railroads emerged as such an important strategic military factor, opposing forces began to try to sabotage the rail operations of their adversaries. There were many new inventions for sabotaging railroads such as rail twisters and devices to blow up railroad bridges and other infrastructure. Some troops specialized in destroying railroad equipment as their sole-role in the war.

The Ruins of Atlanta.

Atlanta, Georgia - 1864.

Photo: Mathew Brady Photographs.

War Department. Office of the Chief Signal Officer.

National Archives and Records Administration.

Still Picture Branch; College Park, Maryland.

Militaries operated the whole of their respective railroad systems in both the North and the South during the Civil War. They did so with typical military precision; thereby making improvements to methods and service that continued beyond the war. As part of this role, the militaries did a lot of construction and repair to railroad properties. There were many additions to the rail system such as permanent and temporary spurs of rail, bridges and other infrastructure during the war. This vastly increased the areas served by railroads in the Eastern United States. Many important innovations such as railroad signals were created while the militaries operated the railroads. Later, the railroad signal would be applied to motor vehicle traffic in the form of the stoplight. Brigadier General Herman Haupt supervised all railroad operations by Union forces. After the war, Haupt managed similar operations for civilian railroads including the Shenandoah Valley, Richmond and Danville, Northern Pacific, and served as president of the Dakota and Great Southern Railroad.

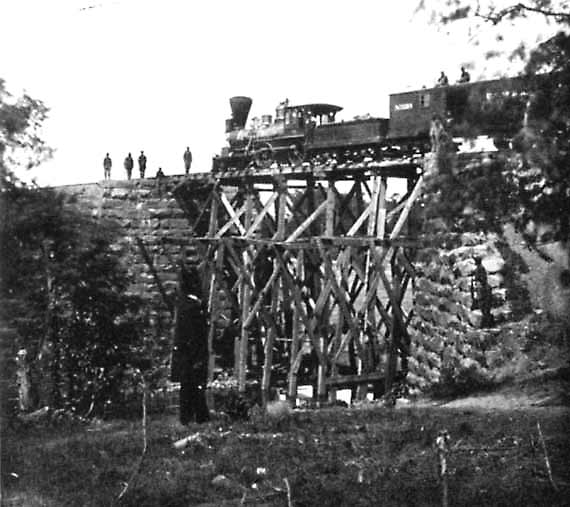

Orange and Alexandria Railroad, Cars and Military Bridge.

Photo: Mathew Brady Photographs.

War Department. Office of the Chief Signal Officer.

National Archives and Records Administration.

Still Picture Branch; College Park, Maryland.

The plan to complete a transcontinental railroad was initiated by President Abraham Lincoln during the US Civil War. Consequently, congress passed the Pacific Railroad Act in 1862 authorizing the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads to build the transcontinental railroad along the 42nd parallel. Notwithstanding, at the end of the war the railroad system still stopped at the Missouri River. Construction began in earnest in 1865; due to great natural impediments it was not completed until 1869.

Joining the tracks for the first transcontinental railroad, Promontory, Utah, Terr., 1869.

Photo: Department of Commerce. Bureau of Public Roads.

National Archives and Records Administration.

Still Picture Branch; College Park, Maryland.

The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 also included the provision and specification for the standardization of rail gauges throughout the United States. This eventually brought about the standardization of the gauge of almost all rail in North America including other countries besides the United States.

Before this time, a multitude of individual track gauges existed in the United States. In particular, the many different gauges of track in use in the Southern States during the US Civil War proved to be a logistical nightmare and demonstrated the need for a uniform rail gauge. When a rail shipment encounters a change of gauge, the cargo must be laboriously transferred to a different conveyance to continue the journey.

Almost all of the track in the United States was standardized to 4’ – 8 ½” guage beginning on May 31, 1886. In 36 hours, thousands of miles of track, particularly in the Southern States, was re-laid by tens-of-thousands of laborers to the standard size. This left only a few special lines in various parts of the country with non-standard gauge railway. Subways, streetcars and mountain railways are most likely to be of non-standard gauge.