Gunpowder became an important commodity during the period when alchemy was the prevailing theory of material composition. Alchemy, while more advanced than many ancient chemical theories, was not equipped with the knowledge to reliably produce a particular substance with consistent results. It was not until the 1880s that some of the most significant erroneous theories of alchemy and early physics were displaced. In addition, nobody at this time really understood how combustion worked or how chemical compounds formed. The problem of creating black powder began to bring some scientific understanding into the workings of chemistry.

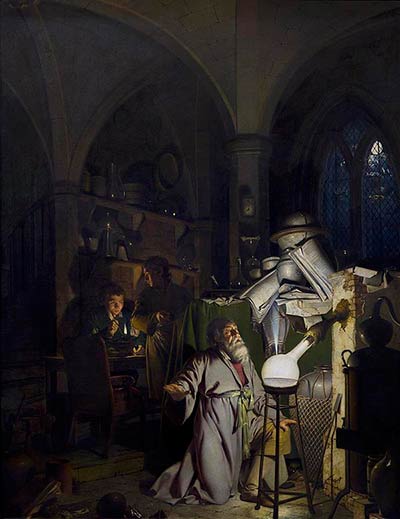

The Alchymist, In Search of the Philosopher’s Stone, Discovers Phosphorus, and prays for the successful Conclusion of his operation, as was the custom of the Ancient Chymical Astrologers.

Medium: Oil on canvas; Joseph Wright of Derby.

Derby Museum and Art Gallery, Derby, U.K.

Around the last quarter of the 18th century, several major breakthroughs in chemistry occurred. First, an Englishman, Henry Cavendish, discovered hydrogen, an important constituent of most combustible materials. Shortly, Joseph Priestley discovered that a certain constituent of the air, now known to be oxygen, was essential for the combustion process. At about the same time, the Swede Karl Scheele independently discovered the same thing.

Roughly concurrently, the famous French chemist, Antoine Lavoisier, researched combustion while he was fulfilling his duties to the French Government as the head of the French Arsenal. Lavoisier studied combustion in hopes of improving the black powder of the day. He most assuredly did succeed in significantly improving black powder and was eventually able to supply improved black powder to the American Colonists during the American Revolution.

The late 1700s were heady days for scientific advancement in France, heady days indeed; and, Lavoisier's research into combustion eventually incorporated the theories of Priestly, Scheele and Cavendish. He also combined these theories with those of Robert Boyle who had postulated the properties of gases a few centuries earlier; and, voilà, modern chemistry was born. As a side note, by 1788 Lavoisier had an assistant powder-making apprentice named Eleuthère Irénée du Pont.

Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743–1794) and His Wife (Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze, 1758–1836), 1788.

Medium: Oil on canvas; Jacques Louis David French.

This magnificent double portrait dates to 1788, when the artist was the standard-bearer of French Neoclassicism. For political reasons, Lavoisier was obliged to withdraw it from the 1789 Salon, and it was not exhibited for a century. Lavoisier was a chemist and famous for his pioneering studies of gunpowder, oxygen, and the chemical composition of water. In 1789 he published a chemistry textbook illustrated by his wife. Despite his services to both the monarchy and the revolutionary regime, he was guillotined.

The Met Fifth Avenue.

Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, in honor of Everett Fahy, 1977.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art; NYC.

This was not a good time to work for the King of France; however, and the French Revolution caught up with Lavoisier a short time later. As was the case with most royals and most government officials, the head of the French Arsenal was compelled to the Guillotine.